Whenever an election brings a new and untried leader to the world’s stage, I think of the iconic picture of John Kennedy alone in the Oval Office. In 1962 the Cuban missile crisis brought us to the edge of Armageddon, and for thirteen days we the people watched and prayed over the loneliness of power and how dependent we were on the courage and the wisdom of one young man.

Understanding violent behaviour in South Africa * Understanding does not mean condoning The current state of affairs across the world has made peace and security a pressing concern not just in policy circles, but also in public discourse. Issues of marginalisation and violence continue to plague numerous parts of the world, with often dire results: The rise of Isis in the Arab world, the prevalence of social unrest in South America and European countries grappling with challenges in their political economy, or poor policing decisions in US. The trend globally has been that intrastate conflict has escalated while there has been a notable decline in interstate conflict. This means that South Africa is not unique in having to deal with what seems like a sharp rise in domestic social tension, in an increasingly democratic and globalising world. The very nature of our international political economy has heightened internal tensions, while limiting the options available to states for reform given the prevailing values of a democratic world. Much of the conflict we are currently witnessing is owed to structural challenges that alienate a broad spectrum of people in different ways. Psychosocial precursors to violence What explains violent and high-risk behaviour, particularly among the young? Jim Cochrane and Gary Gunderson have developed a multi-disciplinary model to explain the five psychosocial “leading causes of life”. In order for a human being to make sense of the world, they need a sense of hope, agency, connections, inter-generational relationships and coherence. If these five aspects are not provided through positive channels, prevalent negative channels step in to allow people to make sense of the world and their place in it. This explains the appeal of gangs — they provide hope, agency, connections and a sense of coherence much needed by our young men and women. Similarly, drug abuse, domestic violence, and even racism, a sense of privilege or xenophobia are passed on as learned behaviour to younger generations through observations and narratives about the world. While not set in stone, unless there is an intervention, children closely observe how their parents respond to conflict and imitate that behaviour. In order to deal with the consequences of marginalising power structures that lead to violent behaviour we need to address the psychosocial concerns that make them possible. Continued structures that perpetuate injustice Despite its importance, it would be a farce to address only the psychosocial concerns that lead to violence. This is an important factor in full development and rehabilitation, but the material concerns that give rise to violence and negative behaviours are pervasive. Controversially, I would like to argue that townships and informal settlements should not exist, they were created forcefully on systems of injustice. To remedy a neighbourhood entrenched with such complexities without addressing the historical challenges that make it possible for negativity to thrive is like putting a plaster on a rotting wound. The violence of apartheid has been restructured in development discourse as inevitable given the conditions that many South Africans were facing. With the advent of democracy the discourse and language surrounding violence shifted, and was reframed as deviant and unwelcome — particularly by those in power who themselves had been part of a violent struggle. Instead of being understood as an outcome of injustice, violence was interpreted as something to be squashed — as Marikana highlights. But as it was then, so it is now, violence represents an expression of desperation for channels of engagement and reform, articulated through learned behaviour. Characteristic during the apartheid era, and early years following Nelson Mandela’s release, was how violence was concentrated in areas of stark deprivation aimed at accessible targets instead of the expected perpetrators of injustice. People incorrectly channelled frustrations about the world to those within reach. This bears a strong resemblance to the recent xenophobic attacks targeting false enemies to express a misplaced frustration at the slow pace of transformation in the country. It cannot be accepted by any means whatsoever. But unless the root causes of these violent outbreaks are addressed, the future does not bode well. The conditions that gave rise to violent and disruptive behaviour and marginalisation have barely shifted. While this is not to say that nothing has been accomplished in democratic SA since 1994, it is perhaps pointing to Frantz Fanon’s ominous predictions for post-colonial states — the structures have stayed the same, while the faces have changed colour. It is also important to ask if development as we now frame it can take place without social disruption. Development might be a zero-sum game if we do not change the rules that determine it. In this way, South Africa is least unique. The global political economy is hostile to the kind of transformation envisaged in our Constitution: free flowing capital, low trade barriers and fluctuating exchange rates might cause established multinational corporations to thrive but have dire outcomes for unemployment, labour and small enterprises — the backbone of any economic development. China’s poor labour conditions and environmental challenges point to this. We need to ask who is paying the ultimate cost for our development, and who is reaping the ultimate reward of our current policy regime. It is a misconception that the political economy is governed by an invisible capitalistic hand that cannot be shifted. But how it should change is still to be answered. The above was originally posted on Mail & Guardians Thought Leader site: http://www.thoughtleader.co.za/masanandingakanga/2015/04/20/understanding-violent-behaviour-in-south-africa/ A white-haired clergyman leans forward in deep, intent conversation with a lady with a shaved head. To the right, three shiny-suited investment bankers cluster around a banking reform activist in his twenties. Over the course of the evening, 60 people drink red wine and laugh together in the heart of London as they watch an improvisational opera singer sum up the findings of the day: the characteristics of a financial system they would collectively be proud to put their name to. This is not a surreal scene painted by Salvador Dali, but rather a workshop convened by The Finance Innovation Lab (which Rachel co-founded). The purpose? To capture the energy created by the financial crisis to bring together people who don’t normally talk to one another to design a new financial system. This group knew that unusual solutions were needed — ones that acknowledge the complex interconnected issues that make a failing system so hard to transform. It can be a daunting task. After all, when a disaster like the financial crisis hits, which problem do you tackle first? Bankers’ bonuses? The failure of legislation? Consumers’ over-reliance on credit cards? It’s clear that a focus on one problem in isolation will be ineffective. To address this complexity there is a growing breed of experts who identify the root causes of problems and set about finding long-term and long lasting solutions. We call them “systempreneurs.” Systempreneurs focus on addressing some of the largest, most complex challenges of our time — from healthcare to food to politics — by taking on our most entrenched and broken systems. Consider this example: the Future of Fish. To tackle the growing problem of overfishing, they mapped the current supply chain, identified entrepreneurs who are working to fix failing parts of the process, and then supported them to succeed. Another example is the Finance Innovation Lab, which hosted the meeting of unusual suspects mentioned above. To create a system that is more democratic, responsible, and fair, they run an accelerator program that supports new business models that could bring diversity to the financial system. To break down barriers to new entrants they also build coalitions of civil society players to jointly lobby for policy change, recognizing the importance of this stakeholder group to open the door for new financial models to emerge. The range of activities systempreneurs undertake is broad and heavily dependent on the system they are working on, but there are some common themes in how they get their work done: 1. They create pathways through seemingly paralytic complexity. Systempreneurs avoid playing the “blame game” and instead point at root causes, highlighting the interconnection between problems. Masters of translation, they use language that connects people to a larger purpose and dissolves sides. They are conveners rather than activists, careful not to align themselves with positions that would harm neutrality, but they often sweep in after public discussion to bring together people who have been disturbed by a debate and turn that energy into action. Systemprenuers are experts in using quick feedback loops to correct the direction of their work. They acknowledge how delicate new projects, new business models, new strategies feel during the creative process so they create safe spaces where pioneers can meet, test, and refine their ideas over and over before being released into the world. 2. They host “uncomfortable alliances” amongst friends and foes. Systempreneurs are skilled hosts, bringing together unusual suspects. They identify the right people to bring to a party – carefully considering the individual’s personal qualities, rather than just a job title. They often have limited power themselves and rely on their role as a trusted, neutral, and honest peer to facilitate difficult conversations between people who don’t agree. They never want to be the star of the show, but they aim to cultivate the conditions for meaningful conversations. They act with humility and welcome people with style, dignity, and gratitude. Systempreneurs appreciate that the process of convening is as important as the content discussed and go to great lengths to empower people who hold potential solutions. They are notorious for their hours spent thoughtfully connecting people by email and know that the secret is to nudge business partners to become friends, encouraging bonds to form in a deeply human way. 3. They create groundswells around new solutions. As Buckminster Fuller said: “You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.” Systempreneurs make things happen. They may spend their time:

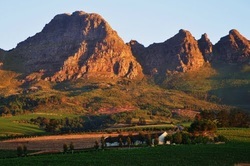

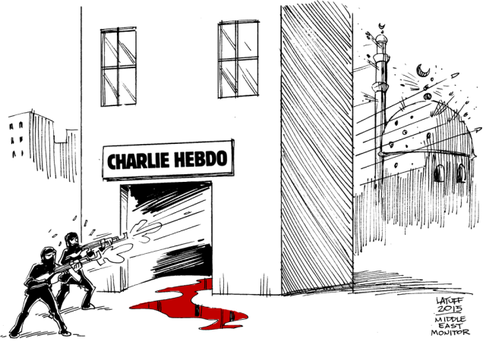

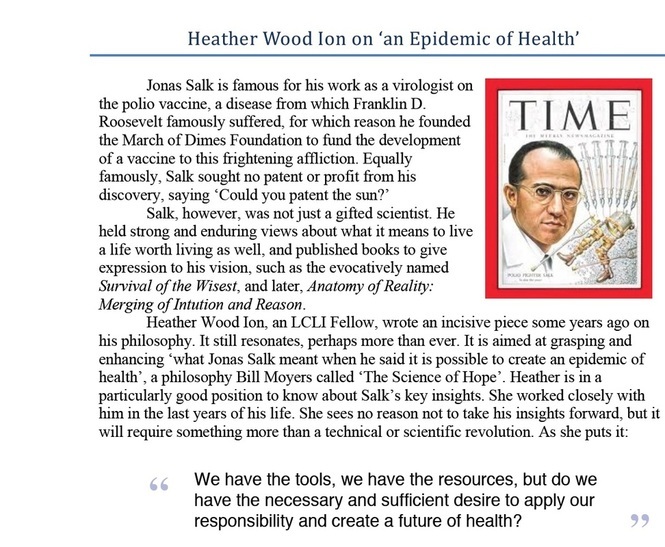

What would boost their chances of success? For starters, we need to find ways to bring the global community of systempreneurs together. They know from their own work that a sense of camaraderie and a place to connect, learn, and share challenges can accelerate success. Yet this group hardly know one another. Second, we need to get them funding. Systempreneurs are still pretty rare, funders often don’t know about them, and their projects don’t fit the typical funding profile. Their strategies are emergent and the outcomes of their projects cannot be easily predicted making it difficult to assess their effectiveness. But funding is critically needed to get these projects off the ground and to sustain them. We need to continue to build a pipeline of these systems changers. And while systempreneurs often incubate others’ efforts as part of their strategies, there are currently no intensive incubators designed specifically for systempreneurs. This group is so busy running their projects that they rarely have a chance to write down what they’re learning, but we need to capture and share their best practices. Changing the status quo sometimes feels impossible. Systempreneurs bring a breath of fresh air to that challenge. They create spaces outside of the current system with a “can do” attitude. They dodge the same-old power dynamics and focus on building solutions that work.  Charmian Love is cofounder and director of Volans, a future-focused business that works at the intersection of innovation, entrepreneurship, and sustainability movements. Follow her on Twitter @volanschar.  Rachel Sinha is cofounder of The Finance Innovation Lab, an award-winning incubator designed to empower positive disruptors in the financial system. She is coauthor of LabCraft: How Labs Cultivate Change Through Innovation and Collaboration. *Reproduced with permission. Original article available at https://hbr.org/2015/02/bringing-an-entrepreneurial-mindset-to-the-worlds-failing-systems  Sprouts find their way through the bullet holes in an old refrigerator in North Georgia. Sprouts find their way through the bullet holes in an old refrigerator in North Georgia. Every religion is dangerous. Like fire, wind and water, religion is a fundamental element of human life that can drown, blast and burn. Religion guides our fear and frames our shame. And it can also strengthen our capacity for the courage shown in generosity, compassion, kindness and decency. It can be a wicked brew and also be like warm French cider on a bitter Winter day. What are those of us who find our hopes in faith to do this week? What do we do when faith has been the language for nearly unspeakable acts? Do we just huddle behind the soldiers, or is there any place for our own actions to be as brave and relevant as the cartoonists like Carolos Latuff poking his pencil into the muzzle of terror? Can mercy be brave as violence? Although it filled up the CNN cash register this week, violence between religions is relatively rare and getting more unusual year by year. I’ve quoted the finding of Daniel Pink in earlier blogs, but worth remembering that all forms of violence continue to decline year over year over year. Most religious violence is between those who share a religion but find its variations deeply threatening. While dozens died in Paris because of their secular differences from Islam, hundreds, probably thousands of moderate Muslims died last week because their 1,500-year-version of Islam embodied the radical hospitality, kindness and sacrificial generosity that fills up the pages of Islamic sacred writings. This is true of every religion. John Calvin burned–literally set fire and watched die–Christian theologians that it would take another theologian to figure out the minor differences in doctrine they were arguing about. He killed Christians not Muslims. I’m a liberal protestant writer who not have survived a week in Geneva. I thought about this when worshipping down the hill from Calvin’s towering grey church with an ecumenical gaggle of english-speaking Christians last July. He would have locked the doors of the World Council of Churches, torched the whole place and everyone in it….and than sung a hymn about it. And Presbyterians are relatively nice people. I’m a Baptist…….which I’m just guessing is more common among the Klan than their up-market Christian cousins. It is always safer to have a radically different idea about god than a moderately different one using the same language. ISIS kills many more moderate Muslims more eagerly than Christians or those who believe in no god at all but humor. Every now and then they may travel to Paris for some especially flamboyant act of horror. But their every day killing is focused on the vast majority of fellow Muslims they find nearby who understand Islam as a faith of mercy and healing. There is not much a Christian can do about radically violent Islam. But it would help to avoid accidentally strengthening the most despicable by implying they know anything about Islam. The “terrorists” aren’t radical about Islam, which is a religion of hospitality and charity; they are radical about their own projected fears, insecurities and delusions which are then wrapped in a weird and horrible way in the vocabulary of Islam. Christians know all about this process. Christian politicians are masters at wrapping their reptilian greed with Jesus’ words. But we don’t say of our nutters “those folks who blew up the Federal building in Oklahoma sure were radical about following Jesus!” Do something to strengthen the moderate Muslims, for whom this is a special time of danger, not only from their traditional nut-cases on the far boundaries of Islam, but now from those of other faiths, including secularity, that will fear anyone they think is a Muslim no matter where they’re from (including Sikhs who stupid Americans confuse with Muslims all the time because of their turbans)(Oh, good grief…..). Sprouts find their way through the bullet holes in an old refrigerator in North Georgia. TC and I took a check over to our friends at the Muslim Free Clinic on Waughtown Street that I’ve mentioned in my blog before. They were today, as they do twice every month, caring for whoever walked in from the neighborhood that needed healthcare, medical counsel or a clue about where to their pill prescription renewed. It is very mundane, as most mercy tends to be. The physicians and volunteers show up and do it because their faith has thought them to do so. They aren’t aiming for martyrdom; just happy to settle for basic grown-up integrity. They are, as a Christian philosopher once said, “grabbing the near edge of a great problem and acting at some cost to themselves.” It is all a Christian, Muslim, Jew, Sikh, Bhuddist, Zoasterian or cartoonist can hope to do with their lives. Do this. Soak in the TV, then turn it off and go find someone who isn’t of your tribe, class, color, faith or opinion and be kind to them in some practical way. Do this. And the God known by every name any human has ever uttered in hope will heal your fears and count you among the living. Do this. By Gary Gunderson  Words matter. Indeed, words are a kind of matter, with weight, velocity and power, especially when humans are talking with other humans about their journeys through life. This became vivid in two days with Stakeholder Health partners in DC followed by two in Minneapolis with Larry and Connie Pray. All four days were about life and its fears and possibilities emerging in the fields of relationships from which come all that matters.  We nurture the life of communities we love knowing they rest on ground in motion. We nurture the life of communities we love knowing they rest on ground in motion. The Stakeholder Health meetings were held in the halls of power of the Hubert Humphrey Health and Human Services Building as people in the government met with those from health systems who shared the basic goal of advancing mercy and justice using the powers of large health systems and and community partners. We had gathered as one of the next steps toward helping each other implement the logic and findings of the Stakeholder Health collaborative learning document (www.stakeholderhealth.org/pdf/).  Fred Smith both embodies and elucidates the concept of the Beloved Community. Fred Smith both embodies and elucidates the concept of the Beloved Community. That widely circulated document laid out some basic framework for moving toward complex human communities in large scale partnerships. Health systems have dropped roughly three bazzillion trillion dollars on technology in recent years, but we still find a big gap in technology that fits the Stakeholder Health model of transformation. The whole drive of Stakeholder is to move toward, not away from, human complexity, so we don’t want control techniques or technologies; we want “relational” technologies. It seems like there should be tools to help that happen without us hospital people turning into programmers. Surely some kid in Bangalore could figure this out. We’re stumped. We aren’t the only ones thinking about community health these days. No idea is currently more powerful or less helpful than the framework of “Collective Impact” promoted widely by the Stanford Social Innovation Review (http://www.ssireview.org/articles/entry/collective_impact). The idea is that a community needs a backbone organization that can bring common metrics and analytics so that everyone behaves in a more socially effective manner. Originally designed to help foundations move toward more collaborative local funding, the idea is now being applied to all sorts of community scale schemes and poppi ang up in all sorts of grant proposals. Not surprisingly, everyone wants to be a backbone. The first rule of medicine is “do no harm.” At community scale it is dangerous to impact something one has not carefully considered. No community is improved by dumbing down humans into collectives that can be impacted, especially by a backbone swung in haste. Two questions: Is the “backbone” the right body part? Don’t we need a heart or mind more? Is “impact” the right verb? Aren’t real places more like gardens? Would any gardener, farmer or forester speak of impacting their garden, farm or beloved woodlands? Metaphors are most dangerous when they encourage us to take the self-serving, sell-reinforcing nature of power lightly. Collective impact emphasizes the role of the backbone organizations which plays into the way local elites LOVE rigid central spine organizations. The same people (often the exact same people) end up populating them replicating over and over again the social dynamics that tend to settle for minor improvement schemes when true transformation is both necessary and possible. This is not a matter of poetic correctness, but programmatic effectiveness. We are foolish, not just impolitic, to think we think we can impact communities into the complex sustained generative processes that produce vital, emergent life? Natural processes rest on humility, wisdom and, yes, love. So Stakeholder Health often speaks of the Beloved Community as the guiding image for our work, honoring not just Dr. King but sharing with him the sense of wonder for the life that God makes possible even in the most difficult and troubled places. This kind of vision calls out practical human models such as the idea of “limited domain collaboration” which assumes partial knowledge and murky grounds for working together, but begins with a hope for what is possible when grown-ups try to lend their best to nurturing the life of the whole. Accurate language for complex human systems is necessary for meaningful success. So don’t try to “impact” my neighborhood; nurture it. You’ll get a lot further faster.  Larry Pray, author of Threshholds and co-author of Leading Causes of Life. “We are all born fluent in Larry Pray, author of Threshholds and co-author of Leading Causes of Life. “We are all born fluent in Larry, still capable of profundity more important than short term recall, noted that you don’t really need to read the words to know what matters in church. You don’t even need to remember the names of those who love you, since the most important thing was not their separate labels but common relationship. “We’re all one body anyway.” Larry says we can speak the language of life without all the footnotes. “We are born fluent in life. It is not just enough. It is plenty.” We find our life as we move through connections and meanings and possibilities and hopes as we generate all that might uplift and nurture Gracia and all she will come to call beloved. We would not speak of impacting her. We hope for far more.  In this piece, fellow Rachel Sinha, reflects on inherited systems and the potential to change their course through time and space. The original piece is available at: http://rachelsinha.com/?p=1029 “At visiting time, we asked our wives to leave, before the prison guards told them they had to” he said. A small cluster of us sat wide eyed and silent as Malusi Mpumlwana, co-founder of the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa and Horst Kleinschmidt, a prominent white anti-Apartheid activist shared story after story of how they found a sense of ‘life’ even in the most oppressive of circumstances. This was one of ‘Agency’. The concept that in that moment they had control over their own circumstances, no matter how small that decision was. And Agency was just one of the ‘Leading Causes of Life’ offered to us as a framework for reflection and discussion at the gathering at Mont Fleur in the Stellenbosch & Helderberg Mountains near Cape Town, this January.  There are five causes in total. The culmination of years of action research and thinking. The roots of the initiative are in public health. A reaction to the repetitive discussion in that sector about ‘leading causes of death’. Gary Gunderson found himself asking unexpectedly at a conference ‘what if we looked for leading causes of life instead?’ Not life as the opposite to death, or life as in happiness, but he and the core team set out to explore how can we might create conditions for life in all its beauty to thrive. What are the five leading causes of life? The five causes are simple;

In essence they are what makes a community feel like it means something to its participants and I have already begun to build them into the design of our workshops and accelerator programmes. But for me they have also promoted deeper insight of a much more personal nature, which I want to write down to understand. I will discuss three. What do the causes of life mean to me? Intergenerativity I’m also reminded that it is not because I’ve worked hard that I have a pretty good life. I’ve done well because I was born with an invisible backpack of privilege (a phrase I learnt from the Labs work with economic justice campaigners). This has been passed down from my ancestors for uncountable generations. And this gives me such a head start, it’s ridiculously unfair. Malusi talked about ‘Black Consciousness waking people up so they could reject the prevailing opinion that the white way of doing things was a universal ‘truth’. My good friend Cassie Robinson talks about ‘systems consciousness’ and for me intergenerativity is about this. Shining a light on the systems that we have inherited, that are invisible if you choose not to ask questions about them, but are there nonetheless.  If we want to be on the right side of history, it is our responsibility to decide whether we support these systems or change them, whether you are the opressor or the oppressed. Agency On a particularly boring holiday a few years ago, I did a fascinating exercise. I drew my family tree, mapping each member and ancestors as far back as I could remember, noting down five personality traits for each person. The process was designed to offer an insight into your family culture. What kind of characters were acceptable? What stories were celebrated, ridiculed or looked down upon? I discovered quite quickly that I come from a long line of strong women who lived life as they wanted it. Women like my Great, Great Grandmother Alice, who married a cartoonist for Punch and gambled the family fortune on the horses. Or my Granny Bird who was witty and talkative and bossy and had no interest in cooking whatsoever, so served spaghetti hoops for dinner almost every night. And of course my Auntie Eileen, a physio, who moved away after a failed relationship, without a care of what her family thought, on an adventure to Africa. I have many of my ancestors’ clothes and I have always worn them. Mad Men cocktail dresses with flared skirts and high necks, matching jackets and fascinators. They are full of style and fun.  Great Auntie Eileen died in the nursing home two months after I left Mont Fleur. At her funeral they read out a message I’d sent a year before, for her 95th Birthday; “It means so much to me to have a woman in our family who has just grabbed life by the horns and went and made it what she wanted it to be. Although we don’t see you often, I want you to know what a big impact you have on us all as a symbol of living your dreams.” The idea of Agency is strong for everyone in my family. That you can move to Australia or Bangladesh, go travelling alone, go sailing and camping and do the job that you find most interesting, because life is an adventure. Marrying into an Indian family, has given me an insight to the other side of this coin. The idea that your life is predestined. that there is a limited range of jobs you should do and that the person you will marry will be decided for you. This is the age-old difference between cultural individualism vs collectivism. And what my English culture brings in Agency it lacks in human Connection. The warmth and love I feel in my Indian extended family is incomparable to the English way of doing family. I’m not sure if it is possible for culture to have both. But what’s interesting is that the systems that are handed down to us from our ancestors are not just tangible like our health system, with its hospitals and doctors and rules and regulations. A cultural system is also passed down. Because culture becomes such an integral part of who we are, how we behave in every situation, it can be very difficult to untangle what you really think, from what has been reinforced in your life to date. I know this because marrying someone from a different culture has held a huge mirror up to my own assumptions. We have different starting points on most things from how often you see your relatives to how many cups of tea you have in a day. Although culture is intangible, it has a huge bearing on whether you are able to easily meet these Leading Causes of Life. Ask any gay child who’s born into a homophobic family, how much connection and agency they feel. It seems to me that in order to really rethink our systems, we need to be prepared to face our cultural starting point and decipher what we’ve inherited and what we’re willing to let go of, for the greater good. Hope Watching the London Olympic Games opening ceremony with the rising pillars of the industrial revolution, made me realise how many of the systems we are now trying to change, have roots in the UK.  For me, remembering history is the key to hope for the future. Realising that the systems we operate within had a starting point. Oppressive regimes, family culture, food, finance and health systems. The way they work are not laws of nature, but they are passed down, inherited perhaps by so many ancestors we have forgotten where they began. These things are made up and therefore we always have the power to change them. Everything passes in time On a night out in my early twenties, my friend Kat and I met a guy who had just finished doing time in Holloway prison.  I asked him about a million questions including how he survived, to which he replied ‘everything passes in time’. His words have stayed with me since. He’s right. Everything does pass in time. Things move on. Challenges become stories and, if we’re clever about it, become words of wisdom that can help others. Systems are ever-changing. Regimes are overthrown, new ones are formed, new markets are built, new cultures emerge based on different values. The next generation comes with new energy to build things differently. And of course we as individuals are not immune to this law. We will also pass in time. I am after all, just another equal branch on our family tree. And there were relatives on my tree who we can’t remember anything about. A whole life and nothing to be remembered by. It makes me think about what contribution I can make that will allow life to flourish, not distinguish it. I have been hugely inspired by meeting Horst, Malusi and others in South Africa. Learning from the example they’ve set of self-sacrifice for things that are bigger than all of us. I am grateful too, for my Great Auntie Eileen, for the lessons she has taught me also. There is no happy ending to this hugely complex mess of thoughts, but in a twist of pure serendipity, two months after I left South Africa, Auntie Eileen’s ashes were scattered in the same spot as my Great Uncle Charlie’s before her. In the mountains above Somerset West, near Mont Fleur.  In this blog-post LCLI fellow, Masana Ndinga, reflects on an article by Shaka Sisulu and the importance of the interegenerative journey. If one has had a childhood similar to mine, then ancestors have consistently been associated with terror. My post-apartheid/colonial upbringing cemented in me a fear of those that came before me - the African colonial library positioned them as ghosts and ghouls reaching ashed fingers across the material-divide to haunt me and make demands of my life. My Christian upbringing affirmed this by categorising these ancestors as demons - dangerous to encounter and consider in my identity. Adopting the faith meant that the dlozis (ancestors) were foe, not friends and my history as a 'son' (not daughter) of God meant that the lineage detailed in the gospels was mine; regardless of how indirect it was: it was mine by virtue of the proverbial blood that I drank at communion and body that I ate. In his article, Ancestors in all aspects of my life, Shaka Sisulu re-positions the ancestors in a more nuanced and inviting light. He chronicles the shift in perceptions of his ancestors through the journey into fathering his second child, recalling the invitations of his grandmother to spend time and receive the blessing that only intergenerativity brings - through time and ages, it weaves a story of coherence from the past through to the present. Sisulu recalls feeling un-whole in the absence of this part of his life and seeking to piece together an identity not just for himself, but for his son too. This journey into understanding one's past deeply resonated with me. I grew up in a strong patriarchal family reminiscent of the neocolonial black middle class of labour reserves across the continent. In particular, my grandfather enjoyed afternoon tea and often dissuaded me from reading Ngugi Wa Thiongo before I read Jane Austen and Shakespeare. I was a confused child, questioning my identity as I searched for coherence and lessons of wisdom in a society that was fragmented. As I grew older, so too did the yearning within me to make sense of my past and to have a personal history of my people and my life. Being fearful of the journey into knowing my ancestors, I decided with great conviction to become an Africanist. I made the presidents, scholars and revolutionaries of the struggle against colonialism my personal history: Nkrumah was my grandfather, Sankara - a family friend, and Biko - my favourite uncle. This process provided me with temporary coherence as I navigated my first years in university. My goal in life was to be like them in thought and purpose. However, I was left wanting for a model for action. When I came face to face with my personal imperfections, as I'm sure those numerous African leaders did, I swayed fervently back to Christianity to be made 'perfect' by the blood of the lamb. Now into my mid-twenties, I am still asking questions about the behaviour and decisions of those before me. How their lives resulted in the perfect circumstances for my life to come into existence. I agree with Sisulu, that there is personal value in knowing where one comes from, but also in sharing that knowledge with those who come after: "Fast forward to my 20s, and there is an uneasiness about me. As if I'm not quite whole. I started to take an interest in my lineage. Where I come from. It was uncanny; I'd seen my uncle go through this years before. He recorded everyone's details and put them into a family tree on his computer. It was cutting edge at the time, and he beamed. I just thought this was the kind of thing that old people do – look at family trees. But as I grew in my knowledge of my parents and their parents and their parents' past I began to feel more comfortable in my skin. I began to feel as though I understood myself better, the better I understood my ancestors' choices." Increasingly, I believe that part of wholeness is an understanding of one's story and forming coherence with one's past, present and future. Hopes and aspirations are intimately intertwined with lessons and yearning past. These become the building blocks of homes and family units - the early seeds of identity are watered herein. Sadly, for many in the developing world, this story is only partly understood. Many decades and histories prior to the 16th Century are still neither fully understood nor appreciated. And many traditions have given way to popular culture as new forms of coherence fill the gap. This is not to say that this historical unknowing is exclusively an African experience, instead I write from my vantage point with the impact on my own personal life. Neither is this to say, that cultural norms and traditions are wholly good. I am fully aware of the immense sacrifice made to allow me to read, vote and marry whom I choose. These nuances, however, do not detract from the importance of knowing one's ancestors and respecting one's traditions. If anything, the journey may help form a sense of ownership and responsibility for the world and the life that bubbles within it - this, for me, is the true key and keyhole to intergenerativity: both opening doors on the journey of development.  We are born to thrive, we live by mending, the glue is Trust. The inevitable in life is something will crack the husk of our lives and from the pain of brokenness will proceed something new growing from the seed which is life. Life will find a way but not without trust adhesive to connect us and our communities back together. As a therapist and leader one of the core concepts that informs the acceleration of innovative and creative work with people and communities is Trust. We run or crawl by the speed of trust which can decelerate our accelerate our best efforts. High trust can accelerate productivity and drive down costs whereas low trust can decelerate productivity and increase costs. Trust is core to life finding a way. Peter Drucker once said, “Culture eats execution for breakfast.”The culture we build in our organizations and communities, resting on trust, is more probable to develop those transformational ensembles that exceed what we could imagine alone. Trust defined as “confidence born of the character and the competence of a person or an organization” (Stephen M.R. Covey) invites a different way of seeing life. One without the other is incomplete. Add to this capabilities and results and the ensemble is complete that inspires high octane trust. My new friend Jim Cochrane might use the word “spirit” which captures more broadly the bent of trust. The web of the leading causes seems to be intertwined with trust as a core adhesive to this jazz ensemble. The improvisation takes on many forms wherever life is finding a way. Steve By LCL Fellow, Steve Scoggin

The attached photo is of Pritchard Park in Asheville, NC where every Friday evening the community gathers for the Asheville Drum Circle. I had the privilege of participating in this life giving event this past Friday while visiting Asheville. In this tiny spot at the center of downtown the community gathers to let the beat of drums and percussion instruments penetrate the soul inviting the body to shake out the rigors of the work week. Young, old, gay, straight and all the colors of the rainbow gather to celebrate life. There is no leader, just the rhythm moving different speeds and cadences taking on a life of its own. There is an energy, coherence, and sense of unity as the drums beat and the song finds its own beginning and ending. The seeming chaos has a beauty and order to it as one drum session ends and another emerges from the crowd of drummers. The square is a petri dish of life as the sounds unite mind, body and soul in a community rite. |

AuthorNotes, ideas and feedback on the 'leading causes of life' framework and impulses. Archives

November 2016

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed